As electric vehicle (EV) adoption in the U.S. continues to accelerate, making direct current fast charging (DCFC) stations more widely available is a key objective of both industry and state and federal government. More than 34,000 DCFC ports have already been installed at over 8,100 locations across the U.S.

Through the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program, the federal government is funding the construction of DCFC stations to be located every 50 miles along designated alternative fuel corridors. The $7.5 billion available through NEVI is projected to add thousands of fast charging stations by 2026, each of which will have a minimum of four 150 kW chargers for at least 600 kW of capacity.

While much activity is underway to make fast-charging infrastructure available, challenges persist with the operation and economics of DCFC stations once they’re installed. In particular, demand charges can affect the profitability of stations for owners, and as a result, present one of the most formidable barriers to the build-out of DCFC infrastructure and the continued growth of EV adoption itself. At current utilization levels, conventional rate structures will continue to challenge DCFC business models.

DCFC presents a unique challenge to electric rate making. High electrical capacity is required to charge an EV over a short period. However, when compared to other high-capacity uses like commercial buildings, relatively little energy is consumed. Conventional rate structures are designed to compensate utilities for this capacity through demand charges. This can result in an exceptionally high demand component of the electric bill for DCFC station owners – particularly at today’s low utilization levels.

With EVs still representing only about 1% of total light-duty vehicles, DCFC stations with low utilization present investment risk. In a 2019 study of dozens of commercial and small industrial utility tariffs, the Great Plains Institute found that, at current levels of utilization, demand charges often make fast charging unprofitable for station owners.

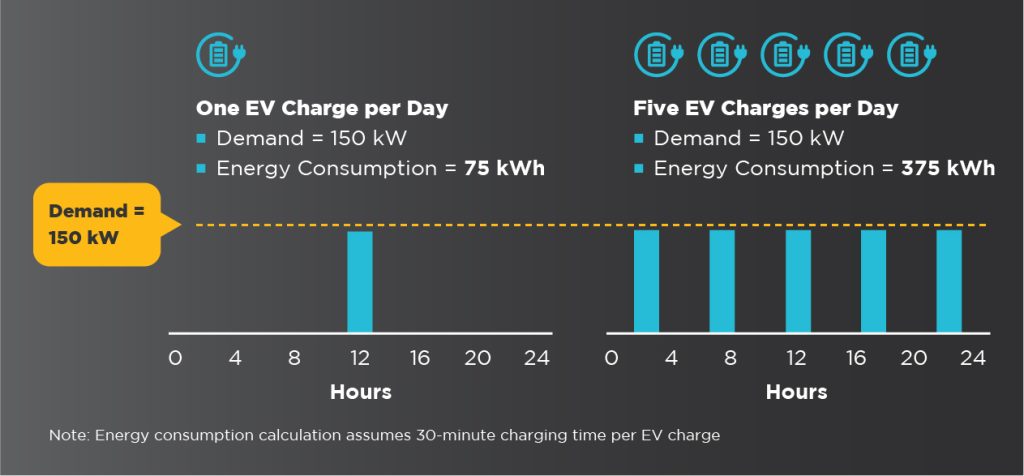

For instance, as shown in Figure 1, a single vehicle charge per day at a hypothetical NEVI-compliant station could result in 150 kW of demand. At the same station, five EVs charging at different times over the day would also result in 150 kW of demand but would spread the demand component of the rate over each vehicle. Therefore, as utilization increases, the impact of the demand charge is reduced.

Figure 1 – Comparing One Charge and Five Charges per Day

To limit the impact that conventional demand charges have on the growth of DCFC infrastructure, electric utilities are developing and introducing a range of alternative structures. These alternatives are designed to lessen the impact of the demand component for a DCFC station until utilization improves.

There are several considerations when assessing which of these alternative structures would be the best option.

Below are some of the key demand alternative structures currently being offered by electric utilities to address this utilization challenge and to support the continued growth of EV adoption.

Under the Demand Charge Holiday structure, only an energy rate ($/kWh) is applied for the initial years of station operation. During this “holiday” period, additional EV adoption, as well as driver familiarity with charging station locations and offerings, is expected to improve utilization. A demand charge component ($/kW) is then re-added and may ramp up over several additional years. The Demand Charge Holiday structure acknowledges the emerging nature of the EV market but is intentional in its application of cost-of-service rate-making principles.

Example: New Hampshire regulators approved a plan in 2022 to offer the Holiday structure with a 75% discount in year one, 50% in year two, and 25% in year three. The demand charge discount ends after year 3.

In the case of the Non-Demand Billing structure, the demand component of the rate is embedded in the volumetric portion of the rate. The utility itself is accepting the risk of low utilization. This structure is intended to provide maximum relief to the station owner and is especially helpful in encouraging charging infrastructure build-out. However, it is subject to potential concerns that the cost burden of charging station investment may be shared beyond EV drivers.

Example: To support the build-out of its regional fast-charging network, the Tennessee Valley Authority introduced a DCFC rate with no demand component in 2021.

The Demand Charge Rebate structure includes both energy ($/kWh) and demand ($/kW) components. To provide relief, all or a portion of the monthly demand charge is returned to the station owner in the form of a rebate. This structure is relatively straightforward to design and implement. The rebate may be removed or adjusted at a future time with limited impact on the energy and demand rate components.

Example: New York regulators are requiring electric utilities in the state to implement this structure utilizing a 50% rebate design.

Under a Subscription Rate structure, the demand charge is replaced with a fixed monthly subscription rate. This results in a more certain and easier forecast of electricity cost for the station owner. Customers subscribe to a pre-determined level of demand (kW) that is offered in blocks. If the maximum demand is exceeded for the month, an overage fee is applied. There is also an energy component ($/kWh) that is applied based on volumetric consumption.

Example: Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) has offered subscription rate plans since 2020. San Diego Gas & Electric Gas & Electric (SDG&E) announced a similar plan in 2022. SDG&E does not apply an overage fee. Customers who exceed monthly demand are instead automatically moved to the higher demand block level in the following month.

Figure 2 – Alternative Demand Structures

While the adoption of EVs continues to accelerate, the build-out of DCFC infrastructure well beyond its current state is a critical next step. However, conventional electric rate structures do not support the economics required to achieve this broad level of investment in fast charging.

To address this need, electric utilities are developing and introducing a range of alternative rate structures. These alternatives each offer their advantages and disadvantages that must be considered in selecting an optimal approach. Utilities seeking to broaden support for DCFC fast charging and overall EV adoption may consider a rate structure that limits the impact of demand charges.

The industry will be watching to see which of these alternative structures are most effective at supporting investment in charging infrastructure and encouraging the continued growth of EV adoption.

View More

Sussex Economic Advisors is now part of ScottMadden. We invite you to learn more about our expanded firm. Please use the Contact Us form to request additional information.